Once upon a time, I was a collector. I gathered trading cards, comic books, pins, stickers, and all sorts of mementos. My collection grew, but ultimately, these items served no real purpose.

Although I haven’t completely let go of the urge to collect, I’ve learned to control it much better. A few years ago, I sold my comic book collection and stopped obsessing over them. Nowadays, I focus on collecting three things: patches from the countries I visit, pins from national parks, and, my favorite, old books about money.

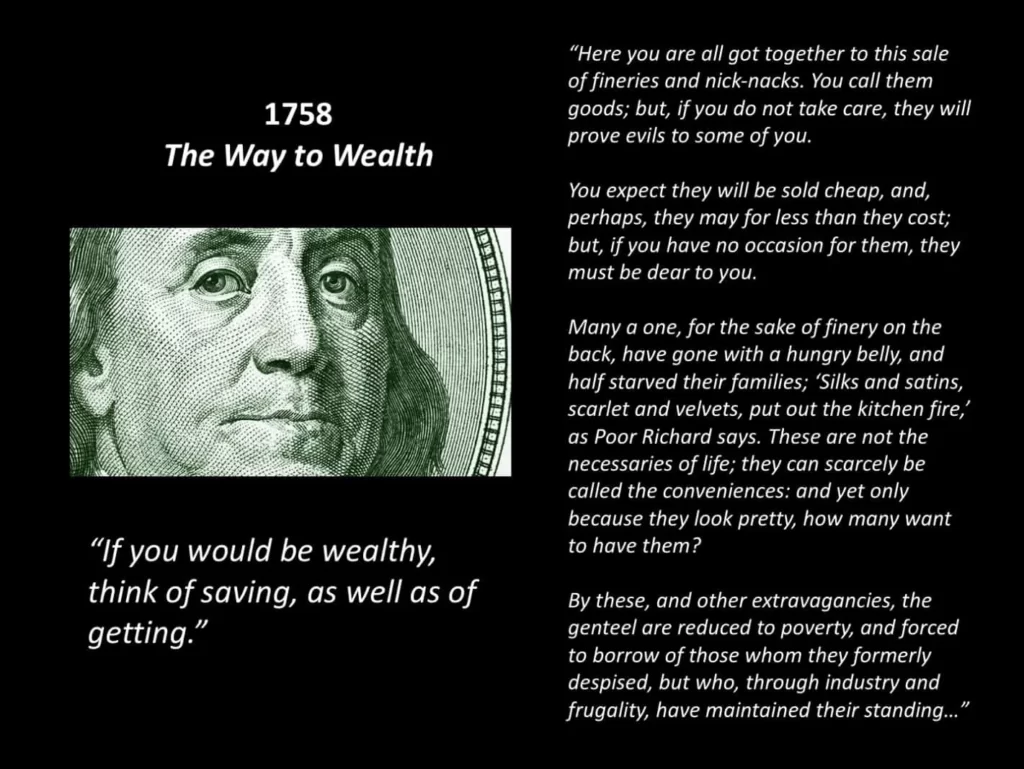

Collecting old money books is a delightful hobby. It connects with my work, and surprisingly, there isn’t much competition in acquiring them because not many people are interested. Well, except for a coveted book like Ben Franklin’s “The Way to Wealth,” which is beyond my reach due to its high demand.

One of the benefits of acquiring these books is that I get to read them. They are quite fascinating! It’s fascinating to trace the history of personal financial concepts across time.

Consider the illusion of “lost economic virtue,” for example. Many people feel that people in the past were better at money management, but this is not accurate. Debt and bad money management skills have plagued us since long before the United States was founded. Our society did not lose smart money management abilities; it has always been the standard.

Financial independence, which is commonly coupled with early retirement (FIRE), is another intriguing concept. While it may appear to be a new trend, examining old money books reveals that similar concepts have been present for a long time. Sure, the concepts have been systematized and arranged over the last decade, but people have been preaching the need of financial independence for at least 150 years, if not more.

Let’s look at the start of this idea of financial independence today, utilizing my collection of historical money books.

I’m currently working on an article that has been in my thoughts for quite some time. Due to limited resources, I wasn’t able to write it until recently. As I continue to gather more old books about money, I anticipate that my insights will evolve. The version you’re reading now is based on a presentation I delivered at Camp FI in Colorado last month. In fact, some of the visuals I’m incorporating here are taken directly from the slides I used during that talk.

The True History Of Financial independence – In the Beginning

The beginnings of the FIRE movement and the concept of financial independence cannot be traced back to a single person or event in history. Despite my growing library of money books, I have yet to find a definitive answer.

However, one of the earliest references to the concept can be found in Aesop’s story of the Ants and the Grasshopper, which is thought to have been penned around 560 BCE. (The grasshopper was actually a cicada in the original Latin.) The original in English is as follows:

The ants were busy on a beautiful winter day, drying the grain they had collected during the summer. Meanwhile, a hungry grasshopper passed by and pleaded for a little food. The ants asked him, “Why didn’t you store food during the summer?” The grasshopper replied, “I didn’t have enough time. I spent my days singing.” Mockingly, the ants responded, “If you were foolish enough to sing all summer, then you’ll have to go to bed without supper in the winter.”

Even though it does not specifically address F.I. or early retirement, this story captures the core of the financial independence concept.

I’m sure there are references to this topic in other ancient writings, but I haven’t looked into it yet. So, for the time being, I am unable to share specific sources. However, if any of you are aware of such references, please share them in the comments.

Moving forward around 2,250 years, we can see the concepts of financial independence in Benjamin Franklin’s works. Franklin emphasized the need for saving as well as earning riches in his 1758 treatise “The Way to Wealth.” He astutely noticed that many wealthy people, obsessed with their love for luxury, often end up impoverished and relying on borrowing from those they once looked down upon.

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau published “Walden.” Despite my qualms about the book and Thoreau himself, it unquestionably provides a solid foundation for the present FIRE movement. When I asked Vicki Robin about her and Joe Dominguez’s inspiration for teaching financial freedom, she highlighted Thoreau directly. And it’s not difficult to see why. “The majority of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” Thoreau famously wrote. He did, however, write the following:

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I’ll call life that must be exchanged for it, either instantly or over time.

You are absolutely right! The Walden quotation is strikingly similar to the explanation of life force in “Your Money or Your Life.” It’s intriguing to watch how these concepts appear in different works.

During the American Civil War in 1864, Edmund Morris released “Ten Acres Enough.” This book described his family’s decision to leave the city and settle in the country, where they grew 10 acres of fruits and berries. Their goal was to acquire self-sufficiency, or what we would now call financial independence.

No responsible man would put the fund in stocks after accepting such a trust and ensuring its integrity. Our country is littered with financial wrecks as a result of events like this…

Morris, like many of his contemporaries, thought stocks were a bad investment. He campaigned for real estate investment. (Note also his use of the word “pecuniary” rather than “financial”). We’ll get back to that later.)

Great trivia! Morris does not refer to the Civil War as a “civil war” in Ten Acres Enough. It is referred to as “the slaveholders’ rebellion” by him. He also uses the word “treason” liberally. There is no nonsense about “states’ rights” being the cause of the conflict, as we hear nowadays.

Coining a Term

In 1872, H.L. Reade released a fantastic book titled “Money and How to Make It,” which has become one of my personal favorites among the books I’ve acquired in recent years. It covers a wide range of topics and is notable for being ahead of its time.

While the title implies that a substantial section of the book focuses on strategies to raise one’s income, Reade goes into a variety of issues. He talks about making money with geese, ducks, and cattle, as well as cheese-making operations. This book is notable for its chapters on “Woman’s Role in Making Money” and “The Brotherhood of Man,” which address social and gender issues. It’s amazing to find such forward-thinking information in an 1872 newspaper!

However, what makes this book particularly noteworthy is that it is the first time I’ve come across an author writing on financial freedom. Here is an excerpt from the book’s introduction:

We have purposefully combined plain practical talk with enough history and story to relieve the volume of any textbook tendency, and believing, as we sincerely do, that no man or woman can read it without receiving a value far greater than its cost, we commend it to the calm consideration of every person who, like the writer, begins comparatively poor and is anxious to achieve what all men should desire and labor for, PECUNIARY INDEPENDENCE.

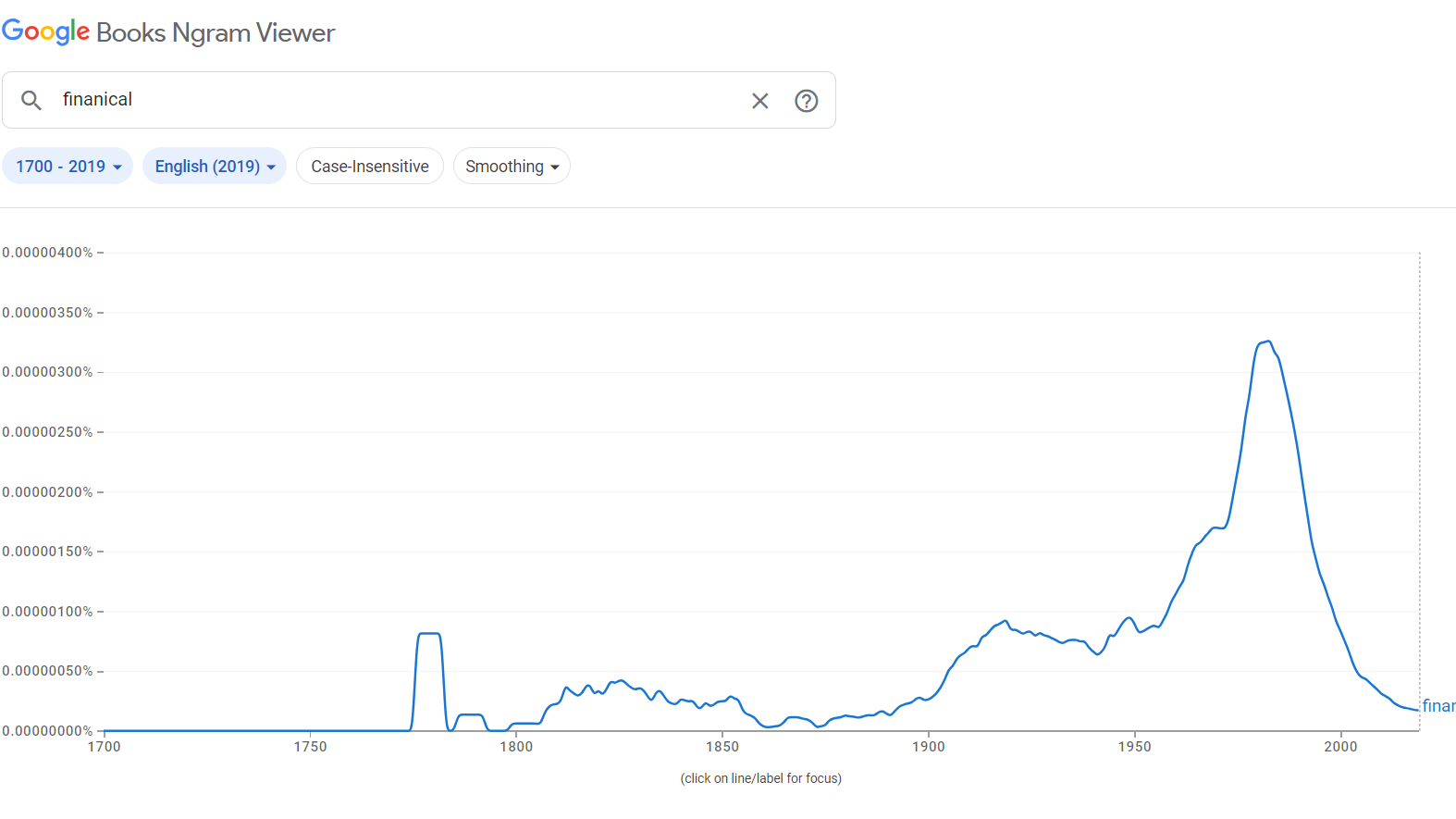

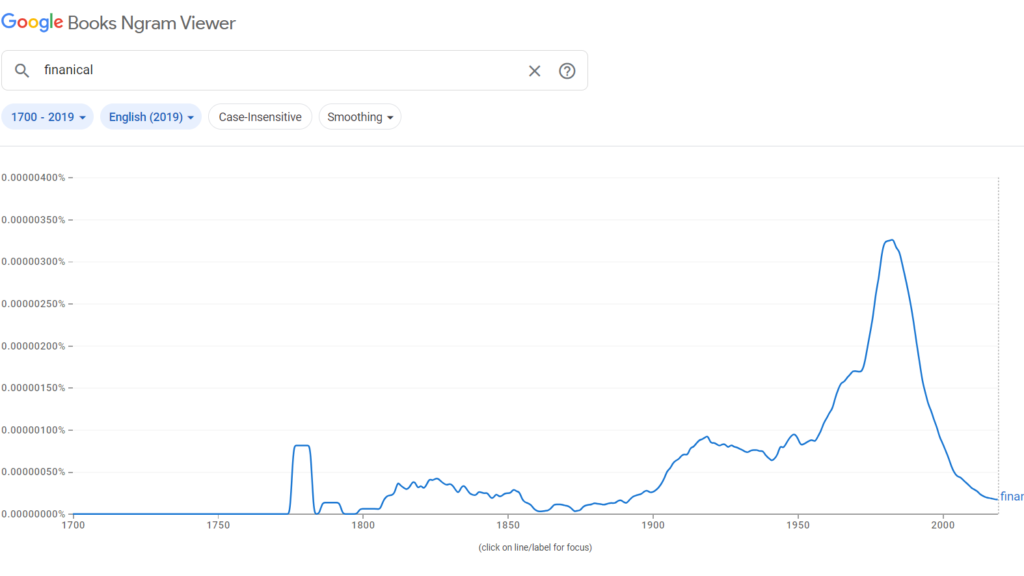

You’ve made a fascinating observation. H.L. Reade’s usage of the word “pecuniary independence” rather than “financial independence” may appear weird to us, but it isn’t when we examine the circumstances of the time. The term “financial” was not as common in 1872 as it is today. While the term “financial” had been in use for several hundred years, its contemporary definition as “relating to money” did not appear until the late 1700s. Before that, the term “pecuniary” was often used to convey the same concept.

Here are two graphs that show the changes in the frequency of the words “financial” and “pecuniary” in written language over time:

It wasn’t until the late 1800s that “financial” replaced “pecuniary” as the preferred term. Reade didn’t write about “financial independence” in 1872 because “pecuniary indepence” was the more frequent term!

Nerdy stuff, eh?

Around that exact duration, another key early F.I. book was published. Thrift was released in 1875 by Scottish novelist and social reformer Samuel Smiles as the final book in a trilogy of personal improvement publications. Smiles first published Self-Help in 1859, followed by Character in 1871.)

In the preface to Thrift, Smiles writes:

Every man is bound to do what he can to elevate his social state, and to secure his independence. For this purpose he must spare from his means in order to be independent in his condition. Industry enables men to earn their living; it should also enable them to learn to live. Independence can only be established by the exercise of forethought, prudence, frugality, and self-denial. To be just as well as generous, men must deny themselves. The essence of generosity is self-sacrifice.

Smiles starts the book by retelling the fable of the Ants and the Grasshopper. For my money — and I haven’t read the entire book yet because it arrived in the mail yesterday — this could be the first book about financial independence…even if the term is never used precisely.

As of right now, I don’t have a definitive answer to the first mention of the term “financial independence.” However, I can tell you about the first appearance I discovered in my collection of antique money books.

In 1919, Victor de Villiers released “Financial Independence at Fifty,” a collection of pieces initially published in “The Magazine of Wall Street.” While the book does not go into great detail about financial independence, the author does present the following definition at the start:

What exactly is financial independence? Independence without reliance on others for advice, government, or financial assistance. The spirit of self-sufficiency or independence from others.

He also offers a graphic depicting “the six ages of investment,” which coincides with my own list of the six phases of financial freedom!

Financial Independence Through the Years

The concept of “financial independence” evolved from its simple beginnings into a more sophisticated and complete concept. The pursuit of financial independence became systematic and structured.

The highly successful “The Richest Man in Babylon” was one of the pioneering publications that established a structure to help individuals achieve financial independence. This is likely one of the best-selling financial books of all time.

“The Richest Man in Babylon” began as a series of brochures issued by banks and insurance firms in the early 1920s. For the first time, author George Clason gathered this material into a book in 1926. The book was revised multiple times throughout the years until it took the form we know today.

As you’re surely aware, Clason proposed the seven commandments for accumulating wealth.

- Begin growing thy purse. (Set aside 10% of your earnings.)

- Control thy spending. (Avoid lifestyle inflation by limiting demands.)

- Make thy gold grow. (Use compounding to increase your money.)

- Keep thine riches safe from theft. (Avoid quick-rich schemes.)

- Make your home a rewarding investment. (Buy a house.)

- Invest in a future income. (Make a retirement plan.)

- Increase thy earning potential. (Inform yourself.)

Along with well-known titles, other lesser-known publications that gave excellent financial advice and championed the ideas of financial independence were written during the twentieth century.

“Gaining Financial Security” by Lansing Smith, for example, was released in 1936 as part of the “The Franklin System” book series. This book, which outperforms most modern money books in terms of quality, may be one of the first to expressly promote financial independence as a concept with a methodical methodology. Here’s an example of the relevance (emphasis mine):

To achieve financial independence, it is critical to understand its enormous and long-term value as a desirable objective. Persistence in trying for it is required, as is your unwavering will to succeed.

It is critical to understand one key issue from the start: your annual income is less significant in the goal of financial independence than is widely believed. There are many people with substantially larger earnings than yours who are saddled with huge debt and unable to pay their financial obligations. In contrast, many individuals with smaller earnings than yours are achieving financial security and even working toward its preservation and increase.

Similar books followed. In the aftermath of World War II, in 1946, John Durand authored “How to Build Financial Independence for a New Age.” Furthermore, other books with the term “financial independence” in their names were published in the 1950s, albeit these later publications mostly concentrated on stock market investment strategies rather than diving into the concept of financial independence itself.

Additional publications addressing financial independence were released in the 1960s and 1970s, supporting ideologies that, by today’s standards, appear relatively achievable. However, it wasn’t until 1988 that Paul Terhorst published what is widely regarded as the first modern FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) book, “Cashing In on the American Dream.”

Terhorst, then 33 years old and a partner at a famous accounting company, began to wonder if he actually wanted to be a part of the never-ending rat race. He pondered whether he had amassed sufficient wealth. After two years of analyzing figures, he realized he could retire if he so desired. He left the workforce at the age of 35 and has been enjoying retirement ever since.

Early Retirement

You’ll notice that I’ve only talked about the origins of the concept of “financial independence” so far. What about retiring early? The current FIRE movement brings these two ideas together under one umbrella. Why don’t older books do the same?

The answer is complicated because retirement history is convoluted.

Retirement, as we know it, has only been around for around 150 years. In truth, throughout the majority of that time, the notion of “retirement” has been in flux. Retirement was not regarded desirable in the late nineteenth century (or the early twentieth century). It was referred to as “mandatory retirement,” and it was strongly opposed.

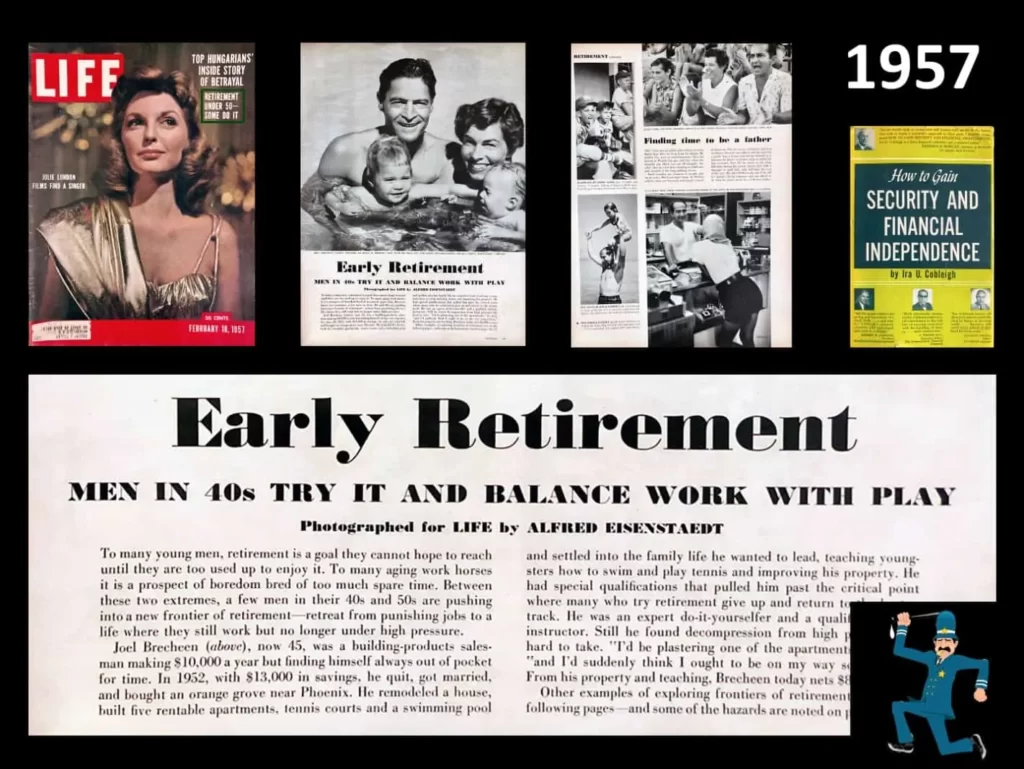

Retirement was a huge societal issue a century ago, comparable to current disputes over immigration or gun rights. Many people were opposed to retirement, but opinions began to shift with the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935. Our modern understanding of retirement as a period of rest after a lifetime of labor began to take shape over time, particularly by the 1950s.

After this shift, the concept of “early retirement” gained hold, and society began to investigate it through books and magazine articles. While academic literature on the issue may not be of much interest to us now, magazine articles provide intriguing insights, especially when they promote early retirement as an opportunity to seek split types of paid work. This is in stark contrast to the prevalent belief in some circles today that “you can’t be retired if you continue to work.” It is worth mentioning that this assumption was false six decades ago and continues to be so now.

FAQs

What is true financial independence?

Financial independence entails having enough income, savings, or assets to live comfortably for the rest of one’s life and meet all of one’s commitments without relying on a wage. A long-term financial plan’s ultimate purpose is to achieve this.

What is the 4% rule for FIRE?

FIRE (financial independence, retire early) advocates strive for a target of 25 times your annual salary in retirement. The amount, known as your “FIRE number,” is predicated on the assumption that you can withdraw 4% of your portfolio annually, adjusted for inflation, without running out of money.

How can I be financially free in 5 years?

1. Pay off all of your debts.

2. Increase your earnings.

3. Save as much as you can.

4. You should spend less than you make.

5. Reduce your unnecessary spending.

6. Invest as much as you can.

What are the basics of financial independence?

It usually entails paying off debt, cutting expenses, and saving and investing actively as quickly as possible. It may also be necessary for you to relocate to a lower-cost-of-living area in order to cut your expenses.

Final Thoughts

Why hasn’t the concept of financial independence received more acceptance? There are various possible explanations for this.

One argument advanced by persons such as Samuel Smiles and adherents of Victorian ideals is that the lack of widespread acceptance of financial independence is due to personal shortcomings. Poor people, according to this viewpoint, persist in their situations owing to poor decision-making. This idea is still prevalent today, with some claiming that personal choices are to blame for financial difficulties. While it is true that individual choices can influence income, I believe that such barriers are more common in the middle and higher classes than in the lower classes. I believe that poverty is often the result of systemic issues, which go beyond individual decisions.

Note: To clarify, no matter the root of poverty, I feel that it is the individual’s responsibility to improve her financial situation. It makes no difference why you’re poor. If you want to get out of poverty, you must make the necessary decisions. After you’ve freed yourself, you may shift your focus to systemic challenges, assisting others to rise as well.

The impact of technology is one of the biggest differences between 1872 and now. When books like “Money and How to Make It” were first published, they had a limited audience. They were costly and not easily accessible to many. Even if someone could afford the book, it was difficult to share the information with others. While lending it to a brother or neighbor could start a small discussion group, most people had to figure out the concepts on their own.

Today, however, financial independence knowledge is available and freely accessible. There is an abundance of information available for those interested in financial freedom and early retirement. Furthermore, technology facilitates relationships with like-minded people via platforms such as Facebook groups, subreddits, blogs, podcasts, and YouTube channels, and in-person meet-ups. Technology has made it effortless to connect with others who share an interest in financial independence and early retirement.

However, I believe that the main reason financial independence concepts did not get on in the past is that most people simply did not care. Some did not believe in the notions’ effectiveness, others did not view them as applicable to their personal circumstances, and many were unwilling to delay satisfaction. Pursuing financial independence necessitates foregoing short-term comfort in order to achieve long-term stability, and as humans, we are prone to prioritizing current demands above long-term planning.

Our species has a myopic view of the world, making it difficult to think about and plan for the future, whether that was true 150 years ago or today. While I do not believe the FIRE movement will die off, I do believe its popularity will stay limited.

The majority of people are unwilling to make the required decisions and changes order to retire early. They are willing to follow the normal path, even if it means working until the standard retirement age of 65, 70, or even older.

I believe that in 150 years, someone will come across digital archives and uncover a plethora of FIRE blogs from 2020. They will be astounded to learn that the concepts they believed were novel had been around for decades. They may use HoloTube to communicate their newfound knowledge of the history of financial freedom and early retirement. According to George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”